Then, at some point—breakthrough! The momentum of the thing kicks in in your favor, hurling the flywheel forward, turn after turn … whoosh! … its own heavy weight working for you. You’re pushing no harder than during the first rotation, but the flywheel goes faster and faster. Each turn of the flywheel builds upon work done earlier, compounding your investment of effort. A thousand times faster, then ten thousand, then a hundred thousand. The huge heavy disk flies forward, with almost unstoppable momentum.

Now suppose someone came along and asked, “What was the one big push that caused this thing to go so fast?” You wouldn’t be able to answer; it’s just a nonsensical question. Was it the first push? The second? The fifth? The hundredth? No! It was all of them added together in an overall accumulation of effort applied in a consistent direction. Some pushes may have been bigger than others, but any single heave—no matter how large—reflects a small fraction of the entire cumulative effect upon the flywheel. … Here’s what’s important. We’ve allowed the way transitions look from the outside to drive our perception of what they must feel like to those going through them on the inside. From the outside, they look like dramatic, almost revolutionary breakthroughs. But from the inside, they feel completely different, more like an organic development process.” ~ Jim Collins, excerpt from Good to Great

I knew in my bones sometime during the age when I was still climbing trees, playing school, and possessing a vague awareness that boys could be charming, that I wanted to write a book. I had no idea as to what kind of book, whether it would be one story or several, or a collection of poems. A work of fiction or nonfiction? I didn’t care about those details.

I would be a writer.

That knowingness became a part of my genetic material and would ebb and flow over the years. I’d tend to it lovingly, the way you gently stir a dying fire, but I’d continue to mostly ignore it. There were times, though, it would sit under my chin, rising, and threatening to suffocate me in order to get my attention.

When I decided to go all in on writing a book, I stood at the base of the mountainous project and craned my neck toward the peak, disappearing in mist. I looked down at myself from the top, through the haze, sizing myself up.

From both vantage points, I considered myself a wholly unprepared and unskilled climber.

I began anyway.

Beginning any project has an energy of promise and shine. I gathered all the books I’d read over the last 12 years, the notes, the half-assed outlines, and the journals filled with pages of questions, observations, and random ideas. Per the suggestion of Austin Kleon, everything went into a Twyla Tharp-esque box.

Now what?

I had so much material, I couldn’t see the through line. Each element of the box excited me and told me I was onto something. I’d have to wade into this ocean of quicksand and flail around to find the connecting dots… the narrative of becoming your best creative self.

I am willing to embrace uncertainty. I am willing to do the work. I have confidence in my abilities. The quicksand held up a mirror and asked me simply, “Are you sure about that?”

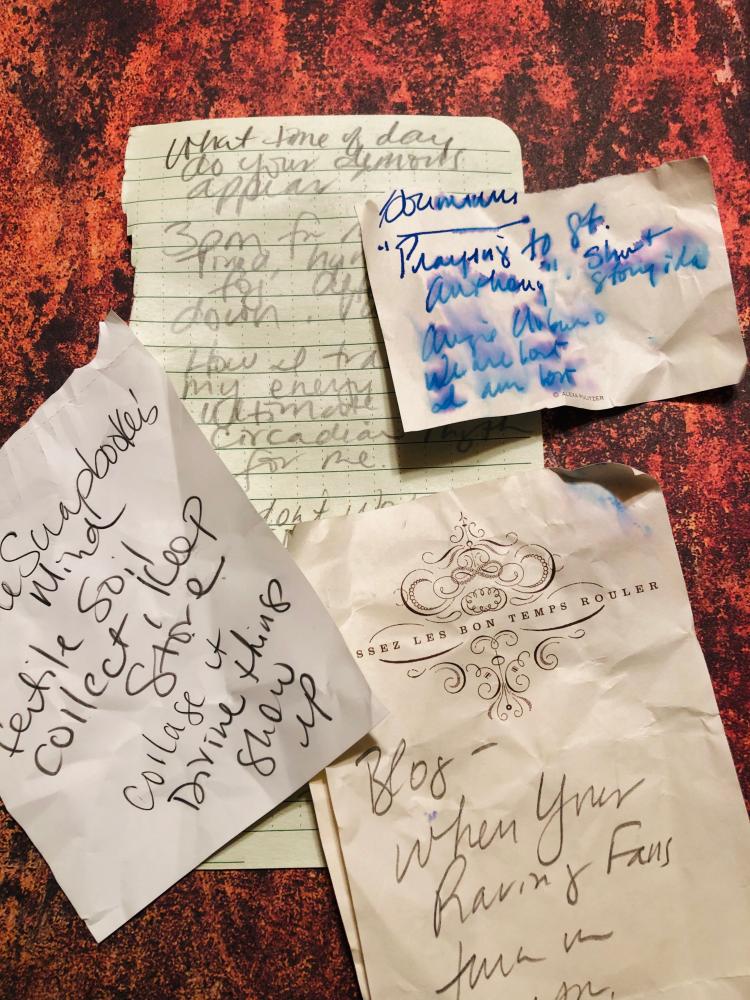

I didn’t know how get all the way across the quicksand, so I did a side stroke over to the one edge I could see and grasp. I began reading through the items in the box, jotting down insights whenever and wherever they came.

Some came in the shower. Some arrived during lap swimming. Others chose to land on a walk in the rain, or in line at the grocery. I kept some kind of paper and pen/pencil with me at all times and scribbled blurts from the beyond.

I noticed that by keeping a scrapbook of my blurts from the beyond, that my collection began creating its own collages of themes, threads, and cohesive ideas. The raw material for chapters!

My first view of how this body of work actually could hang together was a powerful moment of witnessing a sonogram of creativity. Floating within the dark backdrop, I could see the beginnings of life forming… twisting, kicking, and stretching.

I was now a vessel, a conduit, for the rapid multiplication of creative cells within and around me. I was doing the work, but a divine flywheel of creativity (that I had begun turning with great effort at the foot of the mountain) was now gaining momentum.

I was now turning it without heaving effort. In fact, my work transitioned from force and effort to getting the hell out of the way and allowing that flywheel of creativity to turn.

When we look in on the creative process of others, we are often shown the magical moment that the flywheel of creativity has established breakthrough momentum. It appears too far out of our reach, though, so we can falsely believe the game is one we cannot play.

After all, each time at bat, all we’ve known is that grunting, sweating reality of getting the flywheel to make even one rotation. We push with all our might with little evidence of progress. We lose heart before we hit the breakthrough moment of escape velocity.

We are unaware that the physics of the process is as important as the raw material we feed into it.

We are both the flywheel of creativity and the process, while simultaneously being neither.

Gather yourself, your supplies, and your ideas. Begin making that wheel turn.